I went to an immigration conference so you didn’t…

There’s probably going to be audio of all of this. Check reason.org if you’re interested in looking for it, and let me know if I’m not remembering anything correctly.

************

Academic conferences can be funny. You may think they sound like an extended trip to the dentist’s office, but I happily attended one last weekend to hear about immigration. There were three days of activities, but the third day seemed to have an excellent concentration of interesting panels, so that’s the only day I attended. One panel included a couple of constitutional law professors I’ve seen on Twitter, one featured Robin Hanson and Ronald Bailey discussing AI, and one featured Alex Nowrasteh from Cato. There were other panelists, but those were the draws that brought me.

II.

Nowrasteh is an immigration policy expert, and he was hilarious. He had a mild viral moment a while ago on Tucker Carlson’s show when he was confronted with some goalpost moving, but didn’t give an inch. At the conference, he happily assumed the label of elitist and globalist (just like his Twitter bio), at least for part of his pitch. The focus of much of his panel was the economic benefits that would flow from the freer flow of people across borders, but that was relatively boring. (Spoiler alert: apparently those benefits would be huge.)

When asked by an audience member to address cultural arguments about immigration, he said something to the effect of I just played the role of a liberal elitist, but let me put on my conservative hat for a minute. He then proceeded to give a rousing defense of modern American society that left one of his co-panelists at a loss for words. (She basically said wow. Just wow, and had to go in a different direction.) He probably had several iron-clad points, but the idea that stuck with me was that not all cultures are equal; Nowrasteh made perfectly clear that he’s no cultural relativist, and emphasized that he’s quite a fan of American culture. It shouldn’t take courage to say that, but I get the impression that doing so is taboo — after all, it’s a direct criticism of others. (His point was about our freedoms, IIRC.)

Another audience member suggested that the economic argument for immigration, and focusing on individuals’ self-interest, wouldn’t change many minds. The reasoning was pretty intuitive: we care about more than our own self-interest — we care about the communities in which we live. Therefore, if you want to encourage people to support more immigration, you need to convince them that those communities won’t be fundamentally altered for the worse.

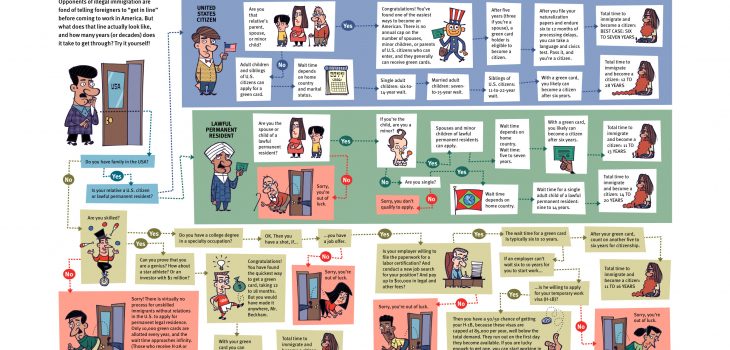

Despite focusing on economics in their main presentations, Nowrasteh’s panel (which included Robert Guest from the Economist, and Ito Peng from the University of Toronto) was broadly in agreement on this point about communities. They somewhat confessed ignorance on the relative merits of various arguments for persuading people, but Nowrasteh had one of his funnier lines about that. He said that the gulf between what immigration law actually is, and what it’s perceived to be, is so monumental that it’s absurd. An example he gave was of an elderly lady who asked him why those illegal immigrants don’t just go to the post office to register — needless to say, it works nothing like that.

III.

My main interest in attending was to hear Robin Hanson and Ronald Bailey talk about robots. Hanson is an economics professor who I’ve heard on Sam Harris’s podcast, and who has written about this topic, and artificial intelligence, including in The Age of Em. Bailey is a Reason reporter who I’ve heard a few times, including a few years ago at a smaller event near home. He’s always seemed to analyze things similarly to me, and to often reach the same conclusions. He kept that up on the panel. (One of Bailey’s points at the prior event was about doomsday scenarios: his book publisher told him that selling catastrophe is easy and profitable, but selling optimism is neither. I wonder how relevant that is to the AI doomsday pushers.)

The AI panel was of particular interest to me because I’ve previously written about the topic. And the week of the event, Hanson and I discussed it at decent length on Twitter.

While the conference was supposed to be about immigration, and this panel was supposed to be on the relationship between immigration and AI to the demographic crisis, it quickly devolved into a discussion about whether robots would result in job loss. This was great for me, because it’s a question on which I have an opinion.

I can’t tell a story about what led to what, and who responded to who with respect to this panel. But some points that I think I recall correctly are:

- Hanson and the person who was brought in to poke holes in his argument (Roman Yampolskiy) both agreed that at some point, AI would exceed human capabilities in pretty much everything. (If you think AI > humans = no more jobs, just keep in mind that that’s a different issue. And see my above article.)

- There are huge disagreements about when that point might be. Hanson provided a historical overview showing that this fear is nothing new, that all previous fears of it seem overblown in hindsight, and was skeptical that this result will occur in the near future. Yet he still thinks it will happen at some point.

- The people who think AI will exceed human capabilities liked to point out that if your fear of this situation is job losses, that you may be missing the bigger problem. I think they’re talking about a Terminator/Skynet-like situation, where robots actively and directly harm us.

- AI isn’t necessarily a substitute for labor; there’s a good case that it’s more like capital, which would obviously make labor more productive overall. (This is the standard story about how we have increasing wealth in our lives.)

- Bailey talked about farming today, and compared it to farming from years ago. He never would have believed that people could make a living selling tomatoes that had been individually cared for like today’s organic/small farm tomatoes are. Call them luxury tomatoes. Yet he thinks we have these types of operations because of technological advances and increased immigration, because those things are how we get more specialization. and therefore more wealth.

- Technological change also creates new industries that will lead to more specialization and therefore more wealth. They cited hairdressers and similar personal care industries as things that didn’t exist until we could grow food without as many people as before. They also (at least Bailey) recognized that luxury tomatoes are a byproduct of this phenomenon, and that people seem to value these things. (If that example doesn’t work for you, consider that an exact copy of the Mona Lisa won’t sell for the same thing as the original, or that we wouldn’t necessarily pay to see robots play sports; we value human talent.)

I enjoyed talking to Hanson and Bailey after their panel about this, as well as Shikha Dalmia, the organizer of the conference. The latter two seemed to understand my point about comparative advantage resulting in plenty of things for people to do, even with advanced AI potentially making people inferior. However, Bailey isn’t on board (yet) with my point that even with a complete advantage over people, AI will not drive people out of all productive activity.

IV.

The first panel was on whether the US Constitution gives Congress unrestrained authority to control immigration. There was a soft consensus on the panel that it’s completely irrelevant for purposes of actual policy today, because the Supreme Court isn’t going to overturn the Chinese Exclusion Act cases that effectively said the answer to that question is yes. But the conversation was interesting, if you’re into constitutional law. (Think, debates about what the Declaration of Independence might have to say about the powers of the King of England, and the sovereign powers claimed by Congress via Article I.)

V.

I could use a lot more intelligent discussion about immigration, AI, and where we ought to be driving policy with respect to these issues. We all could use more intelligent discussion about these issues. If they interest you, then whenever the audio is available from the conference, you could do worse than to listen to the recording of that Saturday in Michigan when these conversations took place.